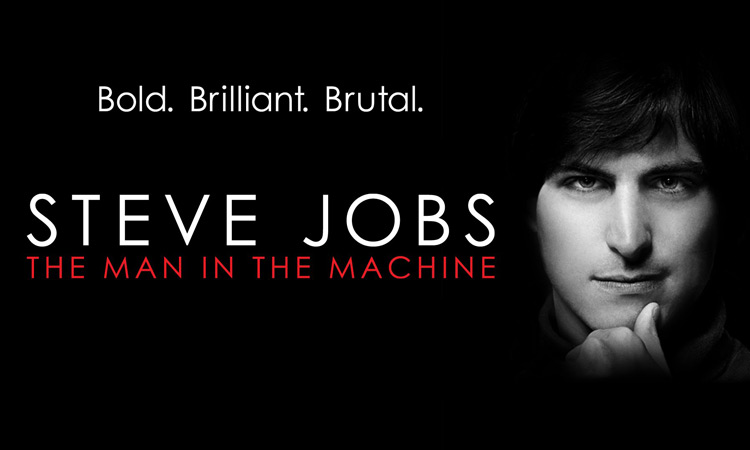

The 13th-century German mystic Meister Eckhart summarized his life’s work when he wrote “the eye with which I see God is God’s eye seeing me.” Meister Eckhart didn’t have an iPhone, but these words can also evoke the subject of the new film Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine. Alex Gibney’s documentary attempts getting beneath the surface of the human being who made possible the existence of the keyboard on which I’m typing. It’s a thoughtful, challenging precursor to Danny Boyle/Aaron Sorkin’s Jobs biopic which is being released next month.

The 13th-century German mystic Meister Eckhart summarized his life’s work when he wrote “the eye with which I see God is God’s eye seeing me.” Meister Eckhart didn’t have an iPhone, but these words can also evoke the subject of the new film Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine. Alex Gibney’s documentary attempts getting beneath the surface of the human being who made possible the existence of the keyboard on which I’m typing. It’s a thoughtful, challenging precursor to Danny Boyle/Aaron Sorkin’s Jobs biopic which is being released next month.

How did someone who built metal and plastic boxes become identified with spiritual wellbeing? Why is Apple able to attract the loyalty of people’s hearts as well as their wallets? It’s partly, I think, because their products enable us users to channel our creative urges—the fact that the products happen to be more beautiful than other computers means that they appeal to people who may value aesthetics more than functionality. The more creative you are, the more you like beautiful tools, and perhaps also the more interested you are certain kinds of enlightenment.

But Steve Jobs, at least in this telling, turns out to have been on the kind of spiritual path that may emphasize inner peace at the expense of external concern. Feeling good on the inside, and treating others bluntly on the outside may simply be the way the journey unfolded for him, with a late life conversion to communitarian ethics interrupted by his untimely death. Of course perhaps the film misses its mark, as Jobs isn’t around to tell us. But Gibney is as interested in why we care so much about his tools and trinkets as in the man himself.

When I switch off my iPhone, the screen is dark, and I can see myself. Intentionally or not, Jobs shepherded technology, and ways of decorating technology, that enable us to see ourselves in new ways. I’m thinking of FaceTime calls, which always seem to include at least a moment or two of checking ourselves out on the screen where we can also see our friends. How strange it is to always be looking at myself when I’m talking to someone else. I’m also thinking of how the silver edging on my MacBook and the back of my phone and iPad feel cold and shiny, and the packages they border are so much more beautiful than Other People’s Computers.

Apple products are tools, but they have also become status symbols, which means they must be treated carefully. Our attachment to brands can become a little too self-important. What they are supposed to do is help us create—organizing words into elegant text, designing buildings that help us live better, establishing and deepening contact with people thousands of miles away, simplifying our lives, helping us remember things we would otherwise forget. This very day, the day that the Lord, or the spirit, or the divine, or the universe (whatever term is most life-giving to you) has made, I know what I’m supposed to be doing because it’s in my iCalendar. I set reminders to meditate, practice self-affirming mantras, and, frankly, to breathe. I make arrangements to see people and complete tasks, including some that (hopefully) offer healing through my vocation of seeking to reduce violence through the stories I tell. Many of us do the same.

The contours of Apple products, like all frequently used tools, are an extension of my personality (it’s entirely intentional that their products are named in homage to ‘i’). When I use them as tools, and when I marry them to a sense of higher purpose, then they become icons through which the light of love can reveal itself. It helps when I see all objects as invested with the possibility of being something more than just “things”—kitchen utensils and cars and pieces of furniture and paper and desks and trees and houses and food and water and paint brushes and photographs and phones and tablets and laptops. The gift of Steve Jobs—and Gibney’s film suggests this was his particular contribution to the world—was to help us invest computing tools with a kind of intimacy.

The computer with which I see God may well be God’s computer seeing me, but what we see depends on how we look. Steve Jobs gave us tools, which may or may not be qualitatively different to other tools—the printing press or the medieval monk’s scribing pen, the internal combustion engine or the horse and cart, the computer or the conversation between two people in the same room. These tools could help us ‘be’ ourselves. They also can get in the way of being ourselves. The genius of his most beloved tool is that it can show us whether we are evolving or decaying, reflected in the shiny granite-like mirror of the iPhone screen.

To find out about Rose’s thoughts on how to live a happier life, click here

Post Disclaimer

This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Please consult a healthcare professional for any medical concerns.