Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926–1938, at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan, is a survey of the artist’s developmental years. During this time, his unsettling and quizzical surrealist style pressed past the permeable boundaries between the conscious mind and nonlogical dream states. Many of Magritte’s images and themes have been absorbed into popular culture, particularly the floating apple obscuring the face of the anonymous bowler-hatted Everyman. His paintings are memorable, but are usually filed away as simply “weird” or “strange.”

“I believe anyone can become more comfortable within the dream world, if only by paying it a bit of attention rather than dismissing it out of hand. Magritte was a studied observer of this world.”

Surrealism as an art movement emerged concurrently with psychoanalysis in the early 20th century and had a similar goal of exploring dreams, desires, and the halls of the collective unconscious, where archetypes and myths dwell. As an artist, I’ve often felt that the creative process is a bit like pearl diving to this primal depth and pulling up something of value. The trick is to become comfortable passing between worlds and temporarily tucking away the logic of consciousness, just as a pearl diver holds his breath. I believe anyone can become more comfortable within the dream world, if only by paying it a bit of attention rather than dismissing it out of hand. Magritte was a studied observer of this world.

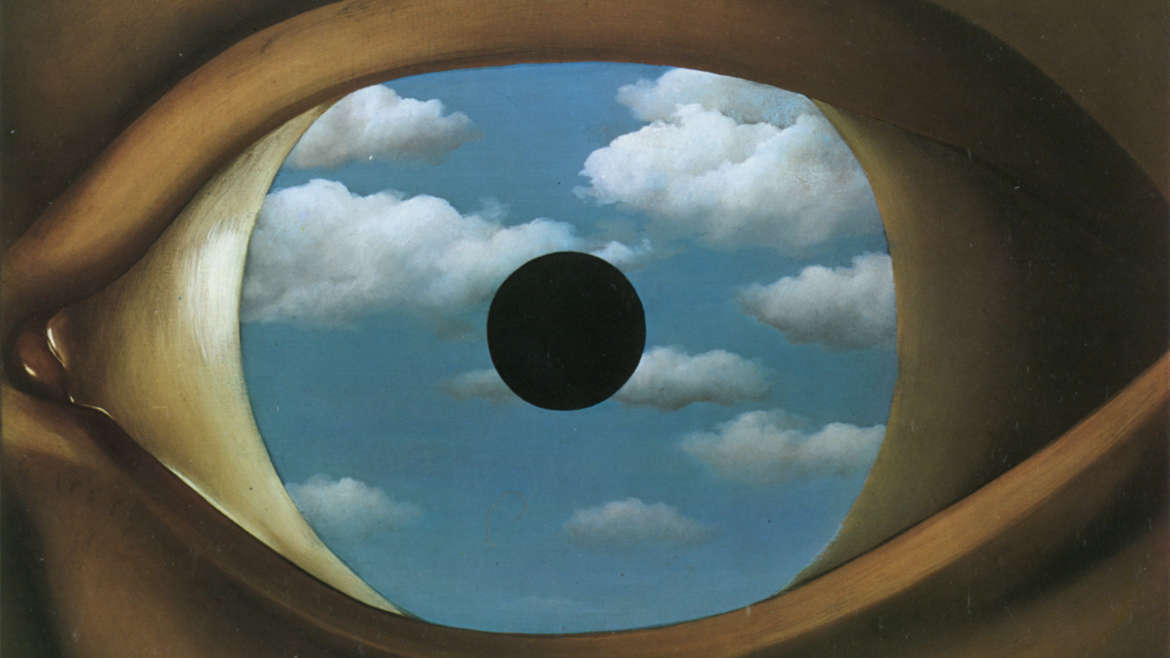

What this exhibit makes clear is that Magritte developed specific strategies for choosing his subjects that have their own poetic logic. His work may seem strange, but it is also strangely familiar—an accurate snapshot from the mind’s inner eye. The unconscious, as explored by Magritte, is not a murky dreamscape filled with haze and mood. Instead, it is a world of painful clarity, making sense to itself, impassively painted as if it were observed rather than invented.

Magritte’s imagery may seem disjointed, but it is never random. In one of his most revealing quotes, he discusses glimpsing a birdcage and somehow seeing an egg instead of a bird inside. He went on to paint that image, one version of which is in the show. An egg is a proto-bird, so its presence in a birdcage has resonance and meaning. Another work in the exhibition, Clairvoyance, carries the idea even further. It is a self-portrait of the artist looking at an egg and painting the bird it will become.

Throughout the show, we see Magritte exploring, experimenting, and posing challenges to the viewer and himself. Girl Eating a Bird (Pleasure) from 1927 depicts a demure Victorian-looking child in a dark dress devouring a limp bird as blood splatters onto her white lace collar. The scene is unquestionably disturbing, but I think Magritte quickly realized the limitations of this aim-to-shock approach. It is not seen much elsewhere in his art. Our contemporary visual culture seems mired in this limited aesthetic, as shocking imagery is never simply implied but is usually shown in numbing, graphic detail. Magritte was able to discover more fruitful ways than this to disturb and perplex the viewer.

The Secret Player, also from 1927, is a scene of two white-suited cricket players in a forest of blue balusters. Above them floats the body of a sea turtle with a head that looks like a cylindrical mass of cigar ash. To the right, a female mannequin wearing a beardlike leather mask peers out of an open cabinet. The scene demonstrates a technique that Magritte would frequently employ: endowing inanimate objects with animate characteristics. The turned-wood balusters sprout branches, like the trees from which they were hewn. Utilizing mannequins, the most humanlike inanimate objects of all, became a favorite surrealist ploy, not just with Magritte. The scene is strange, but it is still traditionally composed, an arrangement of figures in a landscape with proper perspective.

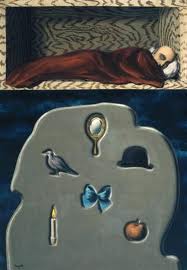

Magritte went further with The Daring Sleeper of 1928, abandoning traditional composition altogether. The top third of the painting recedes into a trompe l’oeil box with a feral-looking wood grain. Inside this womb-like space a bald figure reclines, swaddled in a red blanket. Beneath him is a flat, amorphic shape with a series of indentations. Neatly tucked away into each indentation is a single object: a mirror, a lit candle, a bow, an apple, a bird, and Magritte’s favorite bowler hat. They sit within this dream kit like themes waiting to be utilized. We are no longer looking at a dreamlike scene, but are shown a diagrammatic representation of the dreaming process itself.

Magritte used the inverse of the inanimate-to-animate strategy in paintings like The Secret Double from 1927. It depicts a hollow human head with the face cut off and pulled away from the rest, its gaping interior filled with a fungus-like growth of round bells. The animate has become hauntingly and disturbingly inanimate, as an ostensibly living creature is presented as a mute, manipulated object.

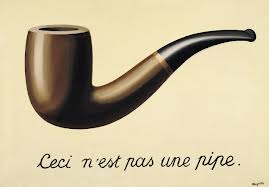

Magritte also reminds the viewer of the inanimate nature of his paintings themselves. A painting, no matter how lifelike, is still a depiction, just an echo of the object it depicts. His most famous and straightforward transmission of this idea is included in this show: The Treachery of Images, a painted pipe with the inscription Ceci n’est pas une pipe (“This is not a pipe”).

A pipe also appears in The Philosopher’s Lamp of 1936, in which Magritte enters the Freudian world of the psychosexual, a favorite domain of the surrealists. It is a self-portrait of the artist gazing calmly at the viewer, sporting a comically thick, phallic nose that is being sucked down into the pipe he is smoking. Normally a symbol of staid domesticity, the pipe has become a perverse siphon of self-consumption. To the left is another exaggerated phallic symbol, a candle extended to serpentine length that slithers up a wooden stand.

As conscious beings, we can never fully inhabit the world of dreams, but the work of Magritte can show us ways through that strange thicket and help us appreciate the “mystery of the ordinary.”

Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926–1938, is at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City through January 12, 2014.

Post Disclaimer

This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Please consult a healthcare professional for any medical concerns.

1 Comment

Jesse

Wow — a masterclass in art appreciation! Thank you for this deeply intelligent and illuminating appraisal of Magritte.